Article written by Riina Bhatia, Research Scientist at VTT, Finland

What would it mean for our policies if we directed innovations not for economic growth and competitiveness, but to meet communally defined needs in a holistic and harmonious way? What does it mean to live a plentiful life in harmony with the nature? And how does this materialize in technologies and innovations?

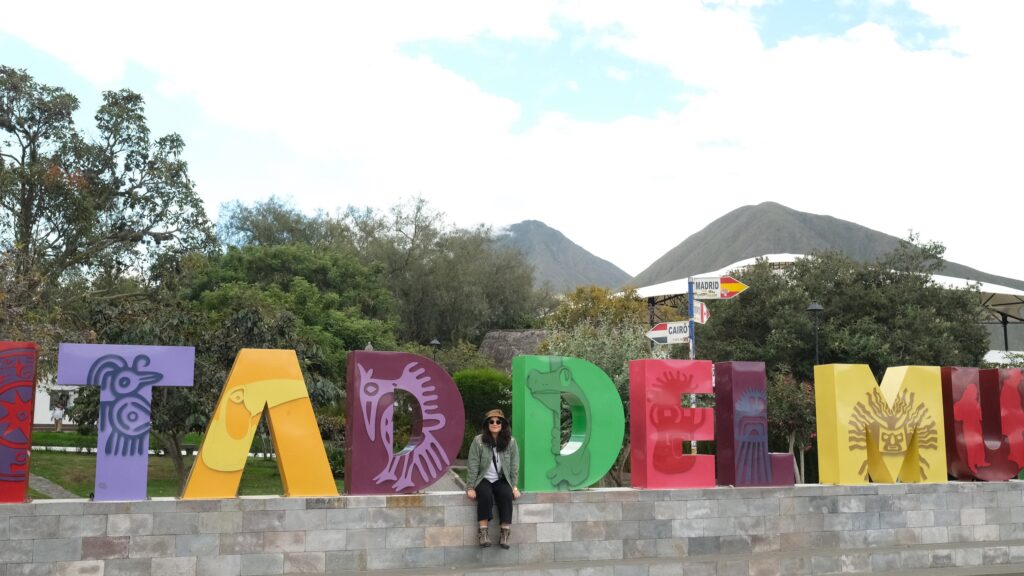

To find answers to these and other questions, the WP3 team embarked on a journey in the Andean region in Ecuador. During an intense two-week field research period the team learned about life, well-being, innovation, and economy in indigenous communities and organizations of UNORCAC, Sumak Yaku and UNCISA. The field visits took place in the region of Imbabura, Ecuador’s province with highest percentage of people with indigenous origin. The field visit was necessary in order to get to know the communities and establish relationships with the communities. Surrounded by volcanos and lagunes, the communities taught us what it means to live a plentiful life in harmony with the family, community, and environment. In other words, we learned what Sumak Kawsay (Spanish, Vida Armónica/ Vida Plena, Eng, Life in harmony) is and how it can inform development of innovations and technologies that serve to live well within planetary boundaries.t

Part of our study in WP3 focuses on alternative understandings on wellbeing, economic growth, and sustainability. We draw on case experiences from Global North and Global South. Ecuador, known for vibrant indigenous communities and the philosophy of Sumak Kawsay, became one of the regions of studies. Sumak Kawsay is a philosophy and cosmovision originating from the Andean region, namely in Ecuador. It became an increasingly popular term to describe alternatives to the hegemonic capitalist development paradigm since the 1990s (Gudynas, 2015), though as a philosophy, Sumak Kawsay originates back in time as a radical critique of all forms of “development at their conceptual foundations”. It defends the idea of diversity of knowledges and interculturality but rejects the idea of wellbeing depending solely on material consumption. Furthermore, in Sumak Kawsay the community is seen to comprise of society and all other living beings or elements of the environments in the territory (Gudynas, 2015). Hence, Sumak Kawsay builds on a strong relational and reciprocal understanding of human-nature relationships. In recent years, the discussion on Sumak Kawsay has emphasized its relevance as a decolonial political project rooted in the historical struggles of indigenous peoples, as well as its interaction within and with the transformative and pluriversal alternatives of the Global South and the Global North (Cuestas-Caza, 2024).

Building on this, the ToBe project is interested in exploring the practical implications and implementations of Sumak Kawsay to innovations and technologies. To unpack this, we visited 17 locations and 13 communities, as well as a community co-operative operating under the organizations of UNORCAC, Sumak Yaku and UNCISA in the municipalities of Cotacachi, Quinchuquí and San Rafael de la Laguna respectively.

UNORCAC, the Union of Indigenous Peasant Organizations of Cotacachi was the first organization we visited. Established in 1977, the non-profit organization made up of 48 communities promotes projects in development with an identity based on the principles of integrality, complementarity, parity, and solidarity. Many projects relate to enhancing access to basic services, like food, land, water, and education. Communities within UNROCAC also work on agricultural production and other productive, sustainable alternatives and the fair marketing of their products.

Sumak Yaku is a small community cooperative established in 2007. It is dedicated to the provision of drinking water services to more than 2300 users in the region on Quinchuquí. It combines water and environmental restoration, efficient use of resources and strengthening the unity and trust of the community.

UNCISA, the Union of Indigenous Communities of San Rafaelwas established in the parish of San Rafael de la Laguna. UNCISA was founded in 1999 and since then, it has ensured the well-being of its nine communities, including the parish center. The organization seeks to support, promote tourism, culture, security, one of the main tasks is the maintenance and improvement of the community cemetery, also they oversee conflict resolution of different kinds as mediators.

In the communities we explored several questions, such as

- Why and how was the organization born?

- What is the understanding of development/Sumak Kawsay?

- How do principles of Sumak Kawsay manifest in the actions of the organization?

- What are the challenges, barriers, drivers, enablers, and motivations of the organization?

- What are the outcomes in terms of ecological, social, and economic sustainability?

- What is the process of organization?

The preliminary findings of the visit highlight that while there are many barriers for realizing Sumak Kawsay in the communities, efforts and work towards shared goals are being implemented on a daily basis. Furthermore, the initial results from the study reveal that organizations established 20-30 years ago to champion indigenous rights have focused on crucial issues like land rights, food sovereignty, cultural identity, continuity, and political struggles, with an acute emphasis on ensuring access to basic services such as water, electricity, and education for indigenous communities. These organizations predominantly operate on communal lines, embedding community-based decision-making (Cabildos), communal labor (Minkas), and profit-sharing mechanisms into their structure.

The communities’ main activities span across agriculture, handcrafts, community-driven eco-tourism, and education, all aimed at enhancing environmental integrity, and social and economic development within a communal economy framework. Central to these organizations’ efforts was the interlinkage of land rights with agricultural practices, food sovereignty, and the rejuvenation of cultural identity and ancestral knowledge, incorporating ecological, social, cultural, and economic facets. However, collaboration with governmental bodies remains limited, primarily to conservation and reforestation efforts, with many communities receiving scant support from local authorities. Projects undertaken often aim at promoting self-identity, self-sufficiency, environmental conservation, and provisioning of basic services, with tourism and agriculture as the most prominent activities. The concept of Sumak Kawsay, signifying harmony with and within the environment, emerges as a guiding principle, although many admit to experiencing a compromised state of living, or alli kawsay (Spanish Buen Vivir, Eng Good Living), due to inadequate basic services, infrastructure and recognition of indigenous sovereignty.

The work with the communities continues in 2024 with a series of co-creative workshops to explore solutions to barriers.

References:

Gudynas, E. (n.d.). Buen Vivir—Degrowth vocabulary. Retrieved March 6, 2024, from https://www.academia.edu/25175735/Buen_Vivir_degrowth_vocabulary

Cuestas-Caza, J. (2024). Sumak Kawsay as Decolonial Post-utopia. En J. Urabayen & J. León (Eds.), Post-Apocalyptic Cultures: New Political Imaginaries After the Collapse of Modernity. Springer International Publishing.